I have a soft spot for CTFs. While CTFs do not reflect the grim realities of penetration testing or red teaming – one key difference is that CTFs have an “a-ha” solution with synthesis going on, they do remain a nice activity one-in-a-while – some challenges are uniquely interesting and the time pressure element is always there (in CTF parlance “blood” or “firstblood” refers to the first one reaching a solution and a significant number of brownie points are attached to them).

One of the most interesting ones I have seen was recently, the “floor is lava” challenge from Amateurs 2025 CTF. I want to share my discovery in solving said challenge, step by step.

What are we up against? (static)

The first step is to identify the file. Using file(1) we get:

nm(1) confirms lack of symbols:

➜ floor-is-lava nm chal

nm: chal: no symbols

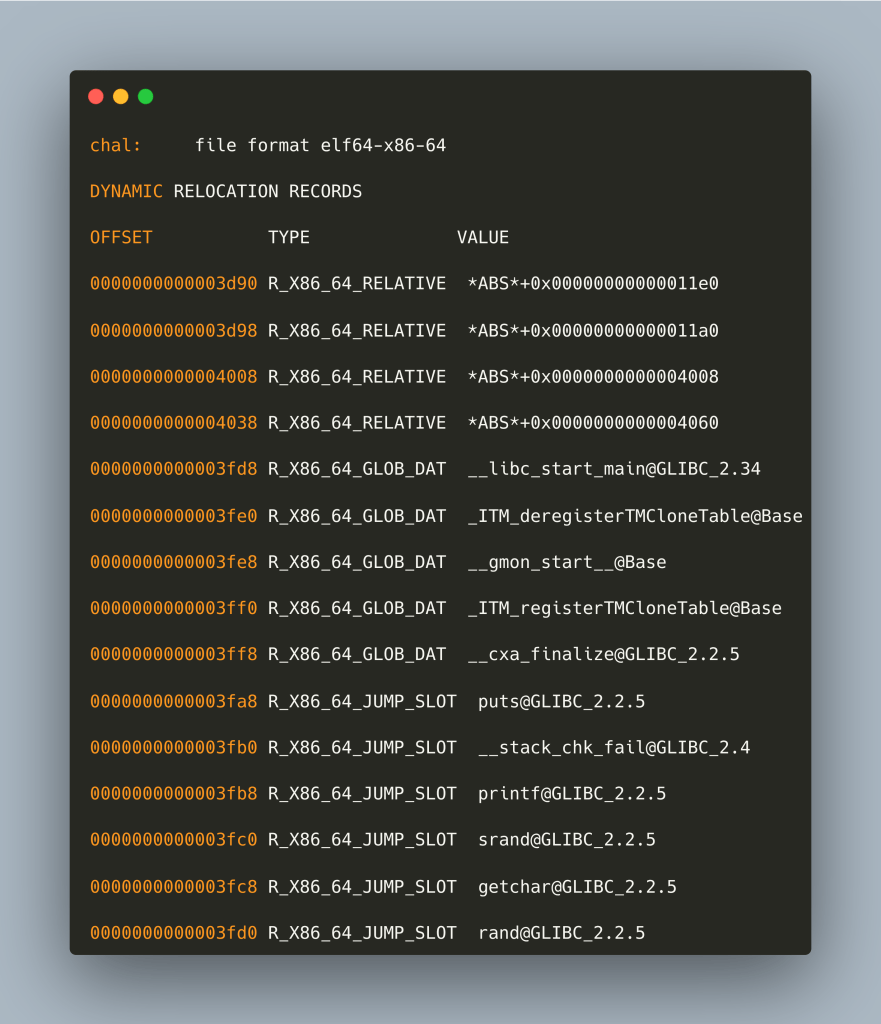

The next step is to check the dynamic imports objdump(1) with -R gives us:

Continuing and examining for ELF section headers (-h) we get:

(for a more compact version you can use objdump -h chal |awk ‘{print $2}’ |egrep ‘^\.’)

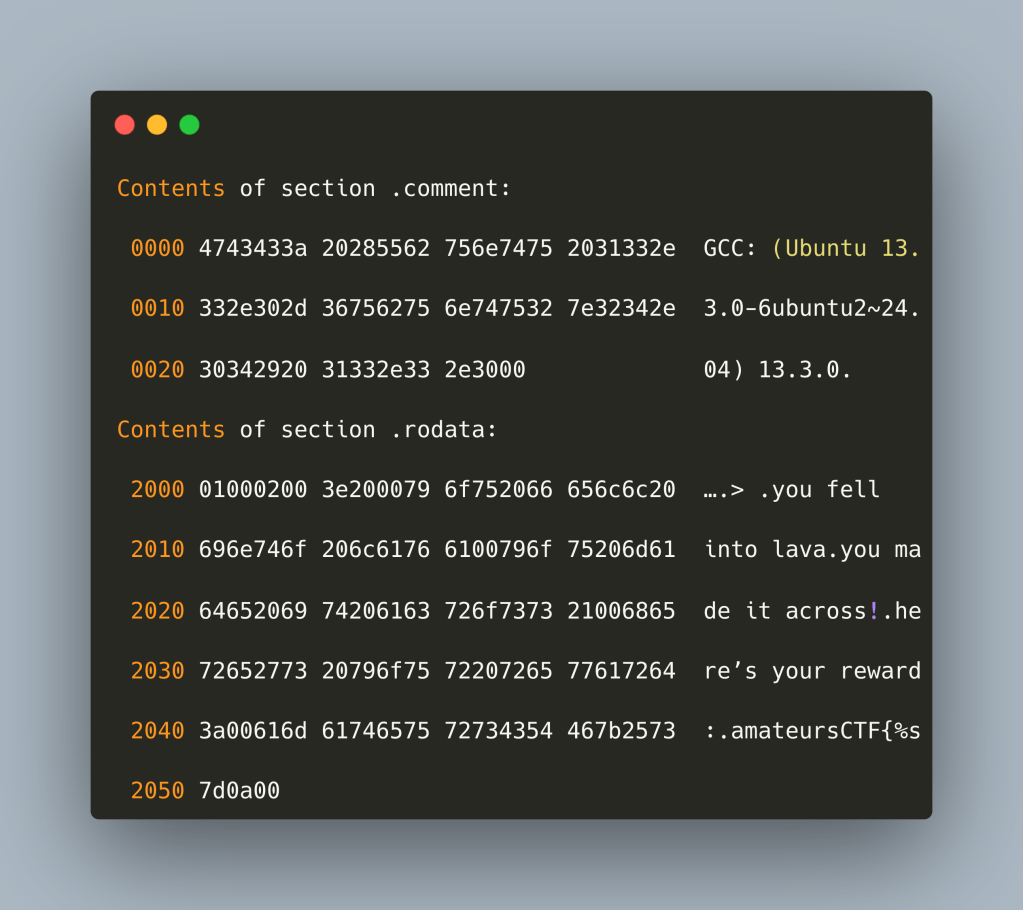

Dumping sections (-s) we get the following:

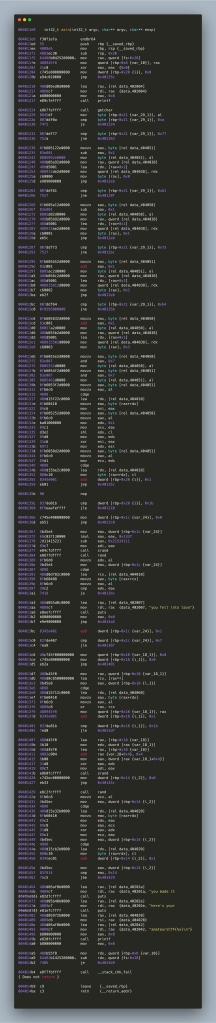

We also notice the presence of note.gnu.property, plt.sec – in addition to the contents of the other sections, it can be deduced that the binary has been compiled with hardening flags. What we have to determine now is if the executable is packed. An educated guess from above is that there are no direct imports of C functions typically used by packers, the file size is relatively small so chances these are not statically baked in and entropy is not unusually high. So, it is time to feed the executable to our reverse engineering tool of choice. Personally, I use Binary Ninja from Vector35 – while there is a free version I am using the paid personal version as I find that capabilities and community support do provide excellent value for money. So the first step after feeding the binary, is to move from x86_64 assembly to a higher level representation (I am using HighIL – other options do exist). Our assumptions hold true and the binary is not packed or encrypted.

I have my IL, what now?

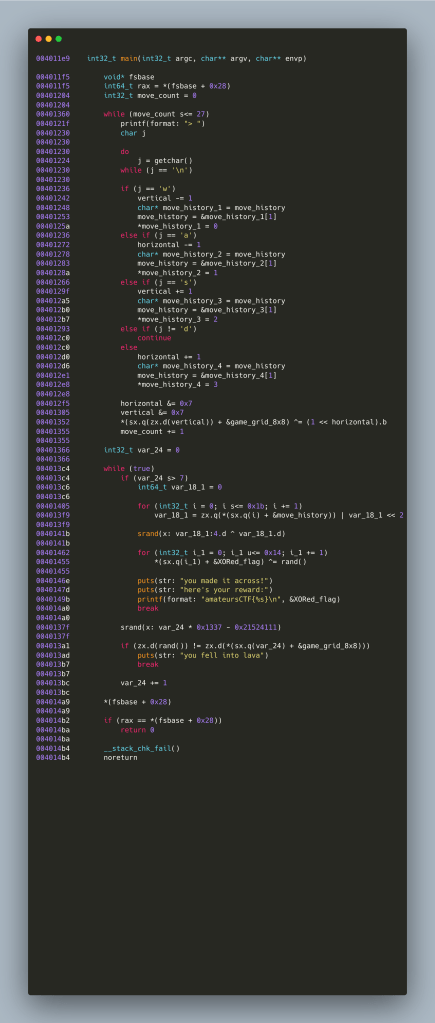

Before attempting anything, let’s start reading the IL we got from Binary Ninja and see what jumps out first. So, there is a counter that starts from 0 and ends in 27 and then it parses a character for being one of “w” “a” “s” “d”. WASD is a very popular control scheme for PC games – especially first person shooters, W moves the player forward, S backtracks, A and D controlling horizontal movement. So, when we enter “w”, the move (adjusting the vertical value by 1 – in this case decreasing) gets recorded into a buffer – given that we have 4 values that means a 2-bit value per buffer cell – 28×2 makes the buffer a 56-bit value essentially. Something that should be noted is that there is nothing stopping the player from entering an invalid character (or sequence thereof) – they are getting ignored and not passed onwards to the 56-bit buffer. Once the buffer is built then the program moves to its interesting verification logic.

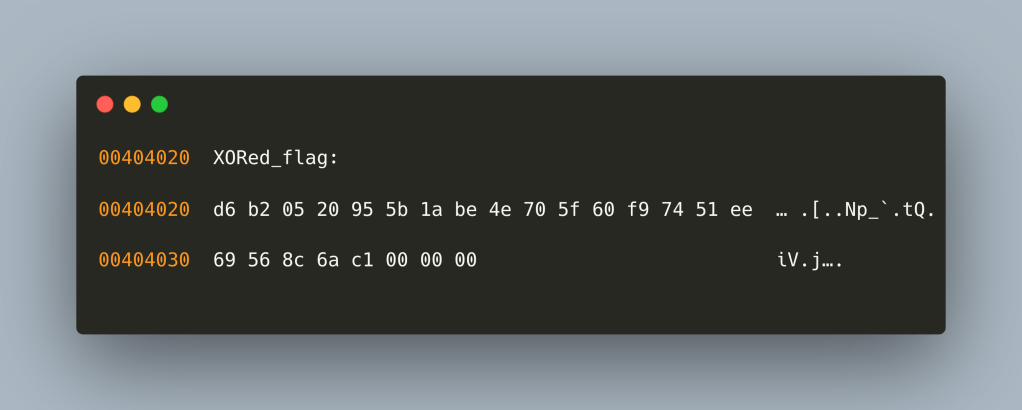

The verification logic has a few interesting strings. Given that our grid is an 8-byte array – each byte being 8-bits then it can be considered an 8×8 grid – essentially an 8×8 bitmap. To protect against static analysis, the author of the challenge does something quite interesting: it seeds srand(3) with a specific value – therefore making pseudo-random numbers generation predictable across runs – essentially an alternative way of “storing” the required values. By travelling within the grid, each move flips a bit in every byte row. Examining the .data ELF segment at 0x00404020 we see a typical NUL-terminated string that essentially is our XORed flag “d6b20520955b1abe4e705f60f97451ee69568c6ac1”

At this point, we have everything we need to get started.

Drivers, start your solvers!

Now that we know what we need to solve, we must evaluate how we get there and start coding a solver.

Brute Force

Brute force in its rawest, non-heuristic form means attacking a 56-bit keyspace. Even in modern hardware, with the CTF clock ticking this attack is impractical. Using some back of the envelope math, a naive bruteforcer needs to cover 4 ^ 28 or 2 ^ 56 or 72057594037927936 – in my lifetime I have lived at a time where 56-bits were considered secure. So, let’s not waste any more time on this.

Tampering

Before proceeding further, a common attack vector in CTFs (occasionally yielding the “unintended solution” status) is to attack the challenge directly (i.e. a little LD_PRELOAD or a little gdb(1) go a long way). In this particular case, since imports are minimal and verification happens piecemeal at runtime, I didn’t readily see a tampering attack path, so scratch that too.

General case

Let’s take a breather and restate the problem: We have an 8×8 grid, 28 moves, each move flipping a bit and we need to reach a certain target state that will yield the correct seed for srand(3) and decrypt the XOR-encrypted flag”. Given that we know the start state and we can calculate the end state, it sounds like a search problem with a few constraints built in, right? With this in mind, some algorithmic candidates do appear. By comparing the end state with the start state, we need to flip 28 bits – which conveniently matches our 28 move limit.

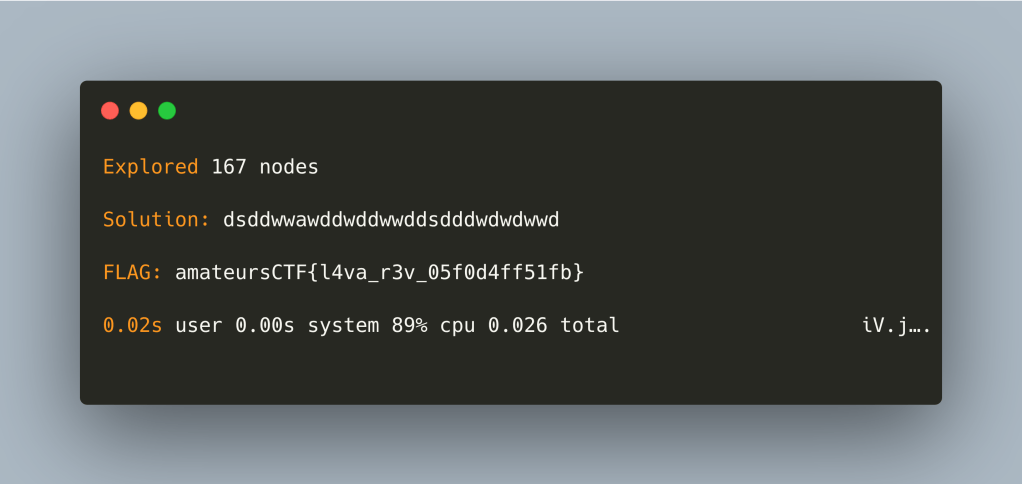

BFS/DFS

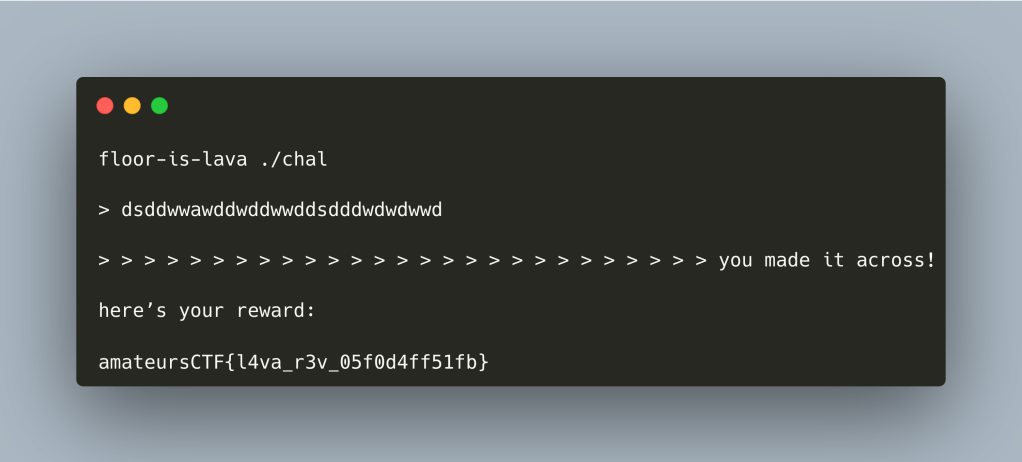

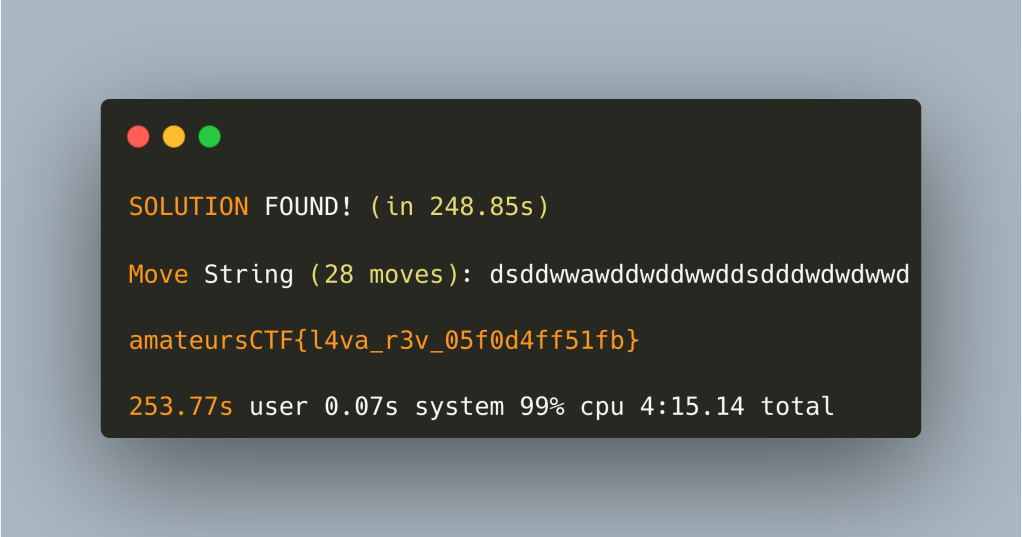

The primary candidates are using BFS/DFS – however the two are not interchangeable. Specifically for BFS the constraints create a state explosion (consider: 8×8 grid, 64 positions, 28 moves) so blindly seeking will not work out of the box. The solution is to switch to DFS with some pruning. Since we are able to know that a) how many more bits we need to flip and b) number of moves left, if a > b, then the path will not yield a solution and can be safely pruned. A python3 implementation gives us the following:

l

Comparing with the binary we get:

It worked! However, is it the most elegant solution? Let’s dig in a bit more.

A*

Having transformed the problem to a pathfinding problem, Dijkstra comes to mind. Given that each step has the same weight as any other one – essentially having no weight and given that we are actively trying to apply heuristics and minimize the problem area, A* emerges (game programmers should recognize this immediately).

Again, a solution was reached in a more than reasonable amount of time. For our problem space, the timing difference is negligible but the important bit is that A* gave a solution by exploring 51 nodes – as opposed to 167 via DFS with pruning.

SAT

Rethinking the problem once more in Boolean logic terms, it becomes a case of assigning binary values (True or False) until all constraints are satisfied – transforming the problem into a Boolean Satisfiability Problem. Boolean Satisfiability problems can be solved using SAT solvers – I picked Glucose3 which is based on CDCL. Given that

- 4 directions that cannot be combined

- Movements can be represented via X,Y variables

- If a cell needs to be flipped, it must be visited an odd number of times – one time only is perfectly fine – keep in mind we are trying to fit everything in 28 moves.

Encoding the above to CNF, we get:

- 5,934 boolean variables: moves (one-hot), positions (3 bits each), gates

- 27,226 clauses: movement logic, binary arithmetic, XOR parity trees

Feeding it to our Glucose3 solver we get:

SAT solvers are powerful general-purpose tools that gave a solution, but at a time cost compared to A*’s geometric approach. Generalization comes with trade-offs, something that an engineer must always keep in mind.

Z3

Now that SAT works, what if we generalize further? SMT (Satisfiability Modulo Theories) is a superset of SAT—it handles boolean logic PLUS arithmetic theories, bitvectors, and more. Z3 from Microsoft Research is a leading SMT solver.

Writing the Z3 solution was actually simpler than SAT—no manual logic gate encoding needed. Running it:

We get a solution, but two orders of magnitude slower than SAT. This is the engineering trade-off: solving the general case introduces complexity and overhead. For a time-critical CTF, DFS pruning would have sufficed.

The time criticality introduces two additional design and implementation trade-offs.

- srand(3) and rand(3) are called directly from libc using Python’s ctypes. While there is a pretty good chance that Python3’s implementation will yield equivalent results, a trade-off was made to directly use the version that definitely corresponds to the ones used in the challenge.

- Skeleton code was created using Claude, what some folks call vibe coding. This provided significant time savings but some common anti-patterns of vibe coding appeared – specifically code generation needed a few prompt revisions to get it to the state needed for further expansion of the code.

Overall, a simple CTF, yet well thought out, led to some interesting discoveries, rewarding algorithmic thinking over brute force or control flow manipulation skills. I inferred the following:

- Generality comes at a cost. The code developed using SAT or Z3, aiming for a general solution is magnitudes slower than A*, a workhorse of pathfinding.

- Proper tool selection is invaluable. In this particular case, using pathfinding algorithms already puts us in the right ballpark performance-wise.

- Heuristics go a long way. While in this particular problem the differences between DFS and A* are not perceivable, in larger problem domains, pruning often and pruning early has a massive payoff, provided sane pruning criteria.

For those watching us from home, here is the GitHub repo (coming real soon).

Until next time folks!

APPENDIX A. x86_64 disassembly and HIgh-Level-IL

1 comment